The long-awaited Irish Electoral Commission will introduce new rules for online political advertising. The proposed measures will bring some transparency into the murky world of online advertising, but they also suffer from a narrow understanding of the issues.

Online political advertising does have benefits. It’s a cost-effective way for political actors – especially small parties and political newcomers – to communicate with voters. However, the international experience has shown that this system is open to abuse and undemocratic practices. It allows political actors to microtarget segments of the population with personalised messages, engage in negative campaigning, spread disinformation, and attempt to influence elections in other states.

The proposed Irish rules will only address some of these issues. During election periods, all paid-for online adverts will be required to carry a label that clearly identifies it as a ‘political advert’ along with a link to a ‘transparency notice’. The notice will provide details about who paid for the advert and how much it cost as well as the intended and actual audience reach. It will also specify whether microtargeting or ‘lookalike’ target audiences were used and, if so, which criteria were used to define the intended audience.

The transparency notice will be displayed in real-time by the platforms and transferred to an archive once the advert has expired. The archive will be maintained for at least seven years as a public resource.

Weaknesses

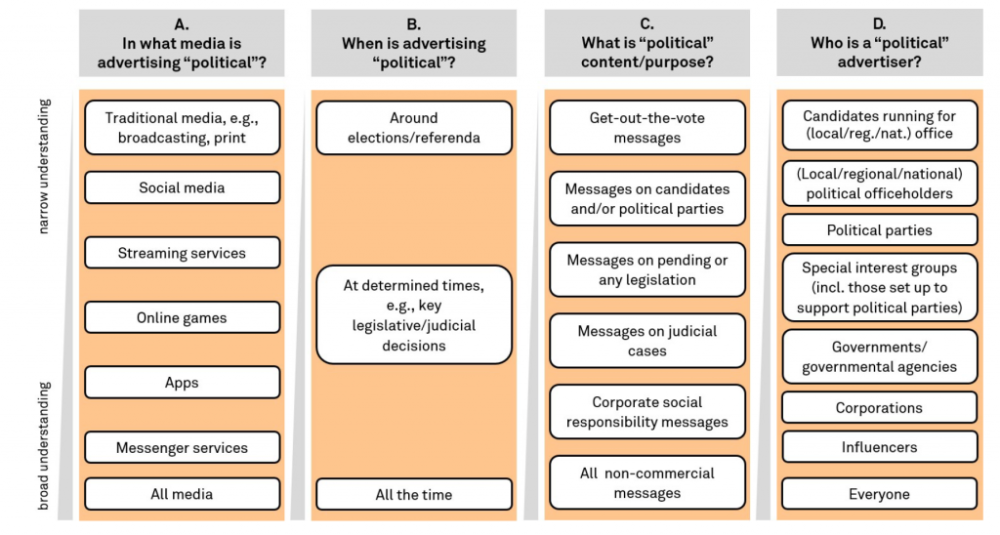

While these measures represent a positive step towards transparency, there are several weaknesses that stem from a narrow conception of political advertising. As Julien Jaursch usefully summarises, any effort to regulate online advertising can be assessed for its broad or narrow definition of key issues.

The proposed Irish rules adopt a narrow understanding:

- The rules will only apply to official campaign periods, but political advertising is clearly not limited to election campaigns. Notably, the Irish rules will be out of step with the EU’s Digital Services Act, which calls for transparent advertising - whether commercial or political - at all times.

- A more universal approach to transparency requirements could also address the role of issue-based advertising by non-political actors such as activists and lobby groups. These actors seek to influence the public by, for example, advocating for legislative changes and promoting protests. As such, this form of political speech also requires transparency and accountability.

- There is no provision to ensure the archive of political adverts will be available in a timely fashion. As far as possible, access to the archive should be immediate to allow journalists, researchers and other actors to investigate political advertising when it matters.

- The proposed measures do not address the content of political adverts. During the last UK general election, the Conservative Party generated a large volume of Facebook adverts that were deemed false or misleading by independent fact-checkers. This problem cannot be addressed without first setting standards for what content is permissible or not permissible.

- The rules for digital and traditional media remain inconsistent. Political advertising on traditional Irish media is highly regulated, but advertising on US-based digital platforms is not. From a technological perspective, this makes little sense as all developments in the media sector point to increased convergence of media channels. As the Broadcasting Authority of Ireland argues measures “should be consistent across both linear and online environments while also having regard to any need to tailor the controls for each individual medium”.

- Finally, there is a question about the flexibility and enduring relevance of the proposed approach. The digital environment is fast moving with new practices emerging all the time. For example, the practice of influencer advertising easily circumvents the proposed rules as politicians can pay influencers to buy ads. A degree of future-proofing needs to be built-in by adopting a broader understanding of political advertising.

Overall, the development of the Irish Electoral Commission

is an important step, but when it comes to political advertising transparency

alone does little to provide public accountability or to ensure democratic

standards are adhered to.

More fundamentally, there is an obvious deficiency in allowing US-based corporations determine what is permissible in Ireland. The dominance of US platforms has led to a largely unquestioned adherence to the US model of permitting political advertising as a form of free expression.

Each platform operates according to its own advertising rules and idiosyncratic definitions. For example, ahead of the 2020 US presidential election, Twitter announced a blanket ban on political advertising while Facebook remained steadfast in its refusal to fact- check political ads.

Instead of waiting for platforms to set rules - often in

response to events in the US - national governments and regulators need to

recognise that they have the power to

define the rules for political advertising in their countries.