When the European Court of Justice (ECJ) declared the EU-US Safe Harbour framework invalid last Tuesday, it raised serious questions about Ireland’s capacity to act as chief guard of European citizens’ data and privacy.

Through low corporate tax, Ireland has courted the major tech companies to set up home in Dublin but the government has largely declined to assume any regulatory responsibility for how these companies behave.

The US has become “Ireland's most important economic relationship” with 700 US companies now based here. In particular, Ireland has proved very attractive to Internet giants with Google, Facebook, Microsoft and Yahoo! all basing their European headquarters in Dublin. Apple’s planned €850 million data centre in Athenry will be the company’s largest in Europe.

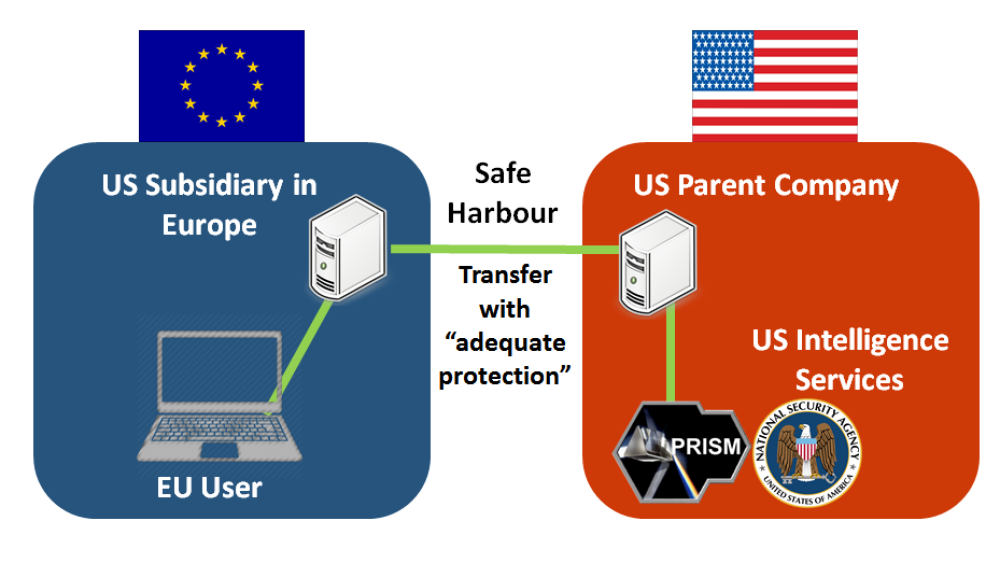

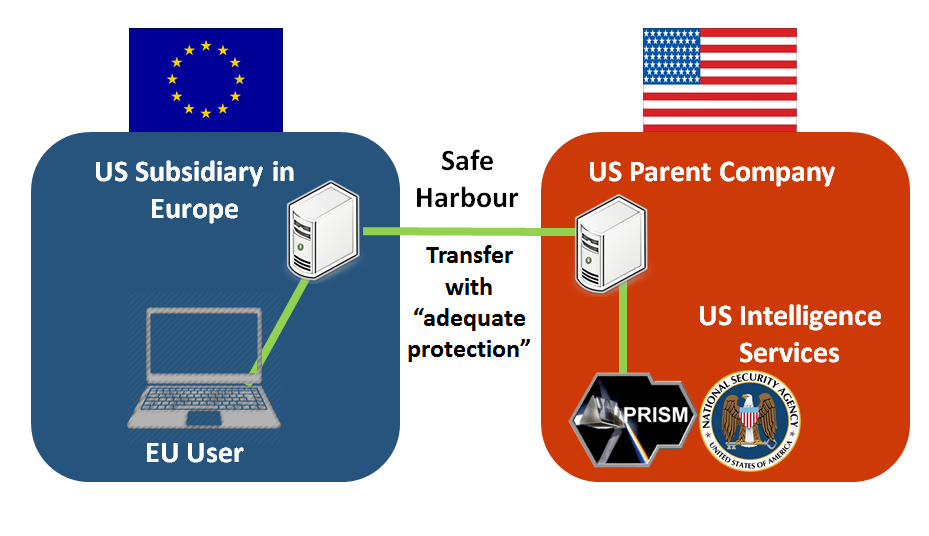

Each of these companies processes vast amounts of data about European citizens and each has passed data to the US intelligence services via the Prism surveillance program. When Edward Snowden revealed the extent of this passive mass surveillance system, EU lawmakers voted to restrict the transfer of European data to outside countries. In reality, the 15 year old Safe Harbour agreement continued without oversight.

Safe Harbour allowed US companies based in Europe to transfer data from their European servers to their American servers. The ‘safe harbour’ aspect merely required that the company gave an assurance that the data would be subject to EU standards of privacy and due process.

The European Commission rubber stamped this agreement in 2000 leaving the poorly resourced and decentralised office of the Irish Data Protection Commissioner (IDPC) with the unwanted role of overseeing the data transfers of US corporations.

A 2013 Irish Times article - “The man in Portarlington who protects people’s data” – presents the data protection commissioner as an avuncular rural guard who favours “an amicable resolution of problems” from his office beside the local Centra shop.

Irish amicability, however, is generally directed towards US companies rather than our fellow European citizens. The commissioner dismissed as “frivolous” the complaint of Austrian privacy activist Max Schrems that Facebook in Dublin enables US intelligence services to illegally access to his private information.

That the ECJ upheld Schrems’ complaint and rebuked Ireland’s ‘nothing to see here’ stance raises doubts about Ireland’s willingness to protect the data over which it has jurisdiction. Some have drawn parallels with Ireland’s ‘see no evil’ approach to neutrality and the use of Shannon airport by the US military. Our compromised neutrality, however, is largely a national issue and one which the country has been reluctant to confront. There is no option now but to confront Ireland’s economic friendliness towards US corporations and our policy obligations on behalf of EU citizens. The ECJ judgment puts a clear onus on the IDCP to investigate complaints and, if necessary, suspend data transfers.

It’s somewhat understandable if the current feeling in the IDPC office is “what have we done to deserve this?” The web has evolved as an information Wild West. Companies seeking to capitalise on private information pit their enormous financial and technical resources against totally inadequate legal systems and regulatory processes. In addition, given Edward Snowden’s revelations, there is little reason to believe that US companies have the capacity, were they willing, to protect users’ data from US security services.

At the same time, US courts have shown little interest in the privacy of non-US citizens. As part of Viacom’s long running copyright case against YouTube and its parent company Google, a US judge ordered Google to provide the viewing histories of over 100 million YouTube users. Thus, a US court was able to take jurisdiction over the data of worldwide web users and furnish a corporation with this strategically valuable information. In settling the case, Google anonymised the data; the court, however, made no such requirement.

What happens next will largely depend on how the US government responds as mass surveillance remains the central issue. Irish policy, meanwhile, will have to satisfy EU regulations and give the fundamental privacy rights of EU citizens the same sacrosanct status that is currently reserved for the country’s low tax foreign direct investment policy.

Subscribe to FuJo's Newsletter.