Russia’s full-scale invasion of

Ukraine on 24 February and the escalation of Europe’s biggest war in the 21st

century has garnered massive media attention. Ukrainian journalists, citizens

and officials have been working non-stop to witness the tragedies of Russian

aggression and provide context, often using social media such as Telegram,

Twitter or YouTube for live reporting of events on the ground. Foreign media

professionals have also been working in and around Ukraine to document the

impact of the humanitarian crisis, the human rights atrocities and war crimes.

They have also reported on the displacement of millions of Ukrainian civilians

as well as other political and economic impacts of the war on a global scale.

The crisis unfolding around the

war has reinvigorated debates about key challenges of reporting on conflicts.

First among these is the challenge of creating impactful journalistic content

that captures the public interest and holds global attention. Closely tied to

it is ensuring the security of independent journalists working in conflict

zones. Third is the struggle to counteract disinformation and malicious

propaganda while prioritizing freedom of information in a highly charged

environment. None of these challenges are new, yet the present moment shows

that the impact of such crises on media coverage and news interest can differ

greatly depending on proximity to the conflict and other factors.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of

Ukraine has notably changed how both Ukrainian and foreign media have been

covering the simmering eight-year conflict after the 2014 Russian occupation of

Crimea and parts of eastern Ukraine’s Donbas region. Since February, many more

Western outlets have sent reporters to Ukraine and surrounding countries. In

May 2022, The Washington Post established a new Kyiv

Bureau – a first for the newspaper – to ground its Ukraine coverage, which

had previously been done from the Moscow office.

To satisfy the heightened interest in Ukrainian affairs, veteran local media organisations such as Ukrainska Pravda and NV (Novoe Vremya) rolled out new and improved English-language versions. The Kyiv Independent, a new website launched by a small team who left the Kyiv Post, became Ukraine’s fastest growing English-language publication, with editor-in-chief Olga Rudenko named one of TIME Magazine’s 2022 Next Generation Leaders.

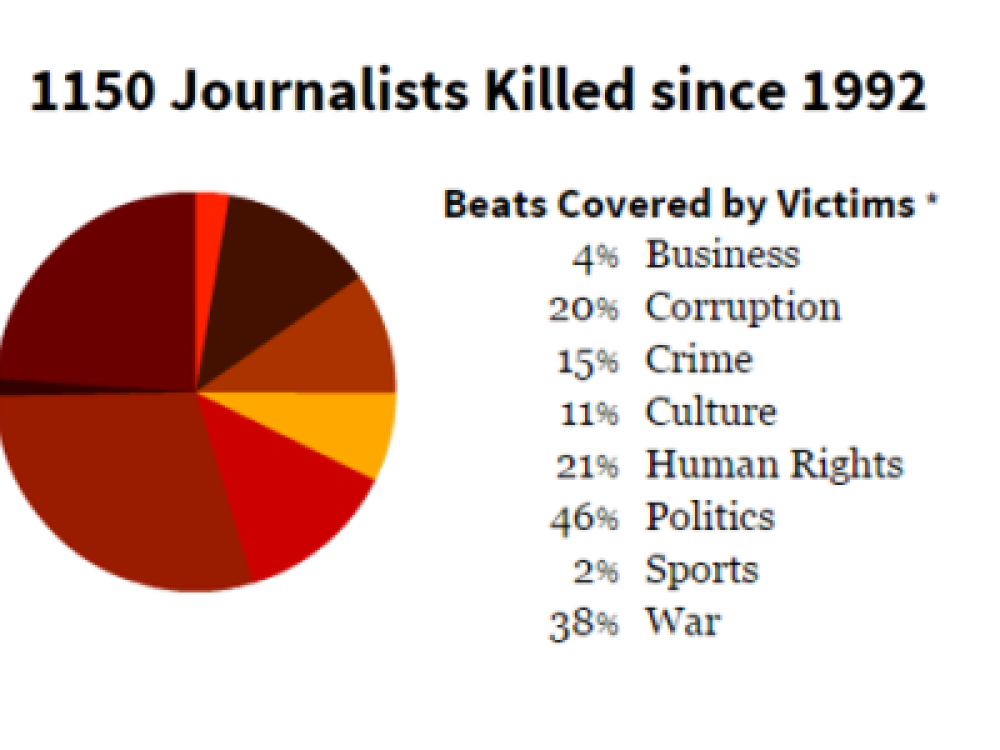

These positive developments have been overshadowed by the tragic deaths of journalists working in Ukraine. According to Ukrainian media NGO the Institute of Mass Information, since 24 February, 29 Ukrainian and foreign journalists and media workers have died in Ukraine, with at least seven of them killed while doing their work.30 In territories occupied by Russia, independent journalists have been prevented from working, threatened, or detained. Media freedom organisations have highlighted the need for more economic support, especially for regional media, and safety training and gear for local reporters and fixers, with campaigns launched by the likes of the Media Development Foundation and support hubs opened by the Institute of Mass Information and Reporters Without Borders

Russian state media outlets RT

and Sputnik have been banned across the EU and restricted on social media as

conduits of state war propaganda and disinformation. Meanwhile, within Russia

itself, new draconian censorship laws have forced the remaining independent

media into exile, preventing journalists in the country from reporting

accurately about the war.

The turbulent events of the war

and their coverage seemingly had an uneven impact on media consumption and news

attitudes globally. A follow-up survey commissioned by the DNR in March-April

2022 to assess how Russia’s war in Ukraine might be changing news habits,

polled people in five countries: Brazil, Germany, Poland, the UK, and the US.

The survey found that, while a majority of the respondents in each country were

following news of Russia’s war in Ukraine at least ‘somewhat closely’,

geographical proximity – and immediate impact – were factors. Attention was

highest in Germany (with 84% following the news extremely closely, very closely

or somewhat closely), as well as in Poland, which borders Ukraine (72%), and

the UK (73%). These countries are close to the conflict and there, the economic

and political fallout is already affecting the lives of ordinary citizens. In

Brazil, both politically and geographically farther from the conflict, around

40% of news consumers were either not following it ‘very closely’ or not

following it at all.

Although not all changes in news

consumption can be attributed to extensive coverage of the conflict, the

follow-up survey found little evidence of the reversal of the key trends in the

prewar DNR survey – namely, decreases in news interest and increases in news

avoidance. In fact, in Germany, Poland, Brazil and the US, the proportion who

said they sometimes or often actively avoid the news had increased since the

start of the war. We know news avoidance can stem from the negative effect war

coverage has on people’s mood, so it is not surprising that the devastating

events of Russia’s war in Ukraine have caused more people to turn away from it.

Despite the increase in news

avoidance, the proportion who said they access news several times a day

increased in Poland by 6pp, as did the overall level of interest in news in the

country (also by 6 pp). This highlights that news avoidance and news interest

are not mutually exclusive. Yet it raises concerns about the impact of the

courageous work of frontline reporters, as it does not seem to have affected trust

in news (apart from a 4pp increase in the UK). Across the five countries,

nearly half or more of the respondents believed news media to be doing a good

job with coverage and keeping people up to date. At the same time, they felt

the media had not performed quite as well for explaining the wider implications

of the conflict or providing a different range of perspectives on it.

In Ukraine itself, the war

brought its own challenges for assessing media consumption and interest in

news. According

to 2021 research by Detector Media, television remained the most common

media channel for Ukrainians to access news about Ukraine and the world,

mirroring DNR’s own findings for the countries in its follow-up survey in 2022.

However, more

recent surveys reveal that Russian military attacks on communications

infrastructure and mass displacement of Ukrainian civilians have seen almost

one third of Ukrainian news consumers lose access to TV viewing in their homes.

A significant proportion of

Ukrainians have shifted their media consumption to online platforms, mixing

digital TV broadcasts with online news websites and social media channels. They

have prioritised mobile access over desktop (reflecting the loss of stable

fixed connections) and have been devoting

more time to online news – with many Ukrainian media outlets reporting a

75- 300% growth in traffic by April 2022.37 Despite heightened news

consumption, the top visited websites are still google.com, YouTube and Facebook.

Ukrainian media outlets also run active channels on messenger apps such as

Telegram, where many Ukrainians go to get news updates, real-time air raid

alerts, and latest casualty numbers. Overall Ukrainians’ time spent online has

dropped, perhaps indicative of the overall information fatigue.

While Ukrainians’ media consumption or news avoidance have been affected by the war far more directly than for media audiences elsewhere, the complex hybrid media environment nonetheless reinforces the value of in-depth reporting and the need for more journalistic efforts to explain the far-reaching implications of the conflict. Enabling local and foreign independent journalists to provide clear and contextualized coverage in a variety of forms and on multiple platforms, and giving them the resources to do so safely, should become the key task for media organisations and others supporting free expression and media development worldwide.

Dr Tetyana Lokot is an Associate Professor in DCU’s School of Communications.

This essay originally appeared as part of the 2022 Digital News Report Ireland. The full report can be accessed Here.